NATIONAL BRAIN INJURY AWARENES S MONTH

TRAJECTORIES OF CHILDREN’S

EXECUTIVE FUNCTION AFTER

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

JAMA NETWORK. PEDIATRICS. MARCH 2021.

By Heather T. Keenan, MDCM, PhD, Amy E. Clark, MS,

Richard Holubkov, PhD, Charles S. Cox Jr, MD and Linda Ewing-Cobbs, PhD

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can

adversely aff ect executive functions

(EFs) that play a central role

in both academic performance

and social interactions.1-4

Executive functions are self-regulation

skills that facilitate sustaining attention,

resisting distraction, managing frustration,

assessing the consequences of actions,

and planning for the future.5 Executive

functions develop by using neural networks

traversing frontal-striatal circuits,6 which

are frequently disrupted by TBI.7,8 Executive

function development extends

in a nonlinear fashion from

infancy into young adulthood,9

with EF components having different

developmental trajectories.

Inhibition and behavior

regulation accelerate rapidly

during preschool years and

continue to develop through

adolescence.5,10,11 Metacognitive

skills, such as working

memory, increase gradually,9

whereas planning accelerates

during late childhood and

adolescence.12 Because skills

in a rapid stage of development

may be more vulnerable

to disruption by TBI than more

well-established skills,13,14 TBI

sustained during periods of

accelerated EF growth may

be associated with greater

defi cit. Understanding how TBI

infl uences the developmental

trajectory of EF in children injured

in diff erent developmental

periods is critically important to

allow targeted intervention for

behavior regulation and metacognitive

skills.15

Executive functions are

commonly assessed using performancebased

measures and behavioral measures

of underlying EF. The Behavior Rating Inventory

of EF (BRIEF)16 is a parent-reported

behavioral measure widely used to provide

an ecological assessment of behavior regulation

and metacognitive EF in everyday

settings and may be particularly sensitive

to posttraumatic diffi culties.17 Prospective

studies using EF ratings over the fi rst 2

years after TBI consistently show a dosedependent

response: children with severe

TBI (sTBI) have greater executive dysfunction

than those with mild TBI (mTBI).18,19

Time course and extent of EF recovery are

not established, with reports at 10 years

postinjury showing mixed results.20,21 Some

studies suggest no recovery of 1 or more EF

components across the fi rst 2 years after

TBI,18,19,22 whereas others found gains.23

Persistent decrements in EF 5 to 7 years

postinjury in children with sTBI suggest

that even when recovery occurs, children’s

EFs do not return to their preinjury trajectory.

24,25

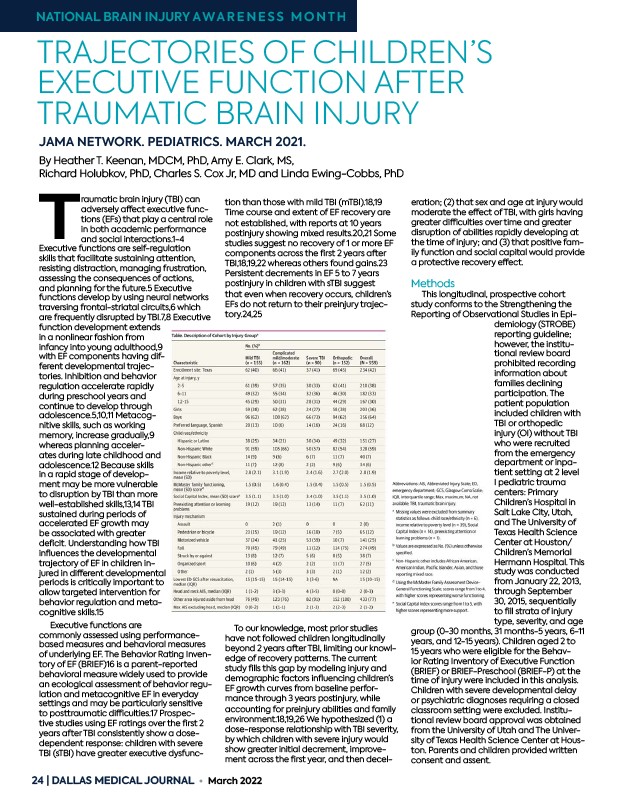

To our knowledge, most prior studies

have not followed children longitudinally

beyond 2 years after TBI, limiting our knowledge

of recovery patterns. The current

study fi lls this gap by modeling injury and

demographic factors infl uencing children’s

EF growth curves from baseline performance

through 3 years postinjury, while

accounting for preinjury abilities and family

environment.18,19,26 We hypothesized (1) a

dose-response relationship with TBI severity,

by which children with severe injury would

show greater initial decrement, improvement

across the fi rst year, and then deceleration;

24 | DALLAS MEDICAL JOURNAL • March 2022

(2) that sex and age at injury would

moderate the eff ect of TBI, with girls having

greater diffi culties over time and greater

disruption of abilities rapidly developing at

the time of injury; and (3) that positive family

function and social capital would provide

a protective recovery eff ect.

Methods

This longitudinal, prospective cohort

study conforms to the Strengthening the

Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

(STROBE)

reporting guideline;

however, the institutional

review board

prohibited recording

information about

families declining

participation. The

patient population

included children with

TBI or orthopedic

injury (OI) without TBI

who were recruited

from the emergency

department or inpatient

setting at 2 level

I pediatric trauma

centers: Primary

Children’s Hospital in

Salt Lake City, Utah,

and The University of

Texas Health Science

Center at Houston/

Children’s Memorial

Hermann Hospital. This

study was conducted

from January 22, 2013,

through September

30, 2015, sequentially

to fi ll strata of injury

type, severity, and age

group (0-30 months, 31 months-5 years, 6-11

years, and 12-15 years). Children aged 2 to

15 years who were eligible for the Behavior

Rating Inventory of Executive Function

(BRIEF) or BRIEF-Preschool (BRIEF-P) at the

time of injury were included in this analysis.

Children with severe developmental delay

or psychiatric diagnoses requiring a closed

classroom setting were excluded. Institutional

review board approval was obtained

from the University of Utah and The University

of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Parents and children provided written

consent and assent.